The Heredity of Naps

Nov. 18th, 2022 11:26 amYou may remember my reporting on Francis Galton's experiment (ostensibly concerning research into heredity) which involved his creating a pocket device with a little hole-punch that allowed him to discreetly rate the attractiveness of every woman he met. I speculated at the time that this might not have played too well with his wife, Louisa.

What I hadn't realised was that he also made observations on Louisa's own family - which happens to be mine too - although these were rather less obnoxious in character. He reported to Charles Darwin in 1871 that Louisa's father, George Butler (for more on whom, see here), had a peculiar way of napping:

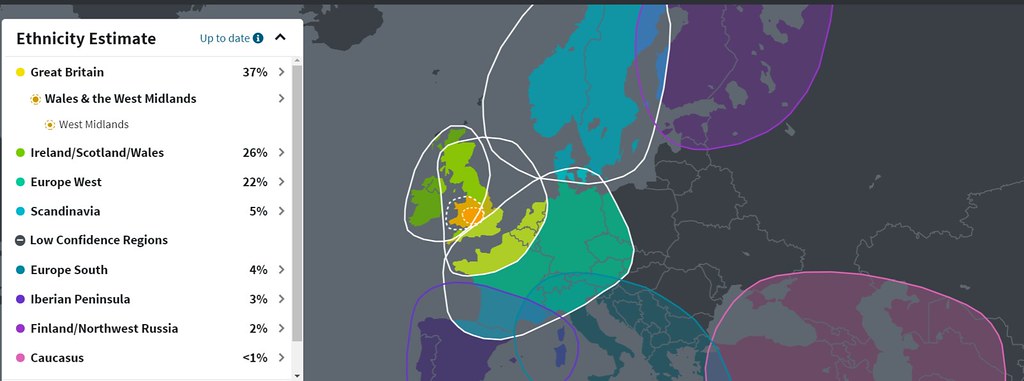

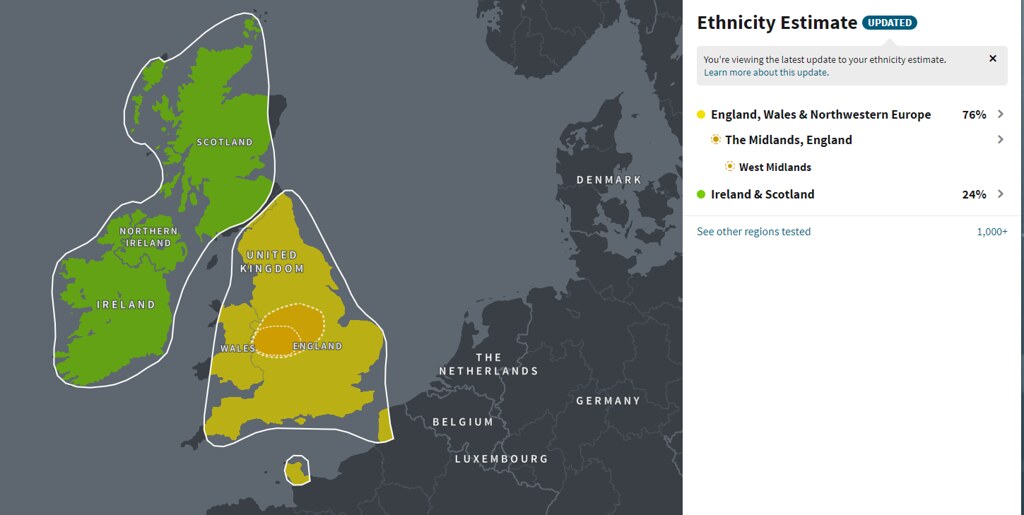

What was interesting to Galton was that this quirk was not confined to George. His son Montagu, and one of Montagu's daughters, had the same habit - and in another letter a few years later he was able to confirm that the same was true of the child of another of George's children, Spencer. He thereupon produced the following map of the heritability of napping with one's arm on one's head:

Here, he puts George at the top of the tree, but there's no particular reason to suppose that the arm-napping mutation started with him. Perhaps it was also to be found in the descendants of George's brother Weeden, my own great-great-great grandfather?

Now, I don't nap in this way myself (though I do often assume this posture when lying in bed), but I'm sorely tempted to do a round-robin of my various cousins.

On the other hand, Francis, perhaps Montagu et al. got the habit from observing their respective parents (or uncles or cousins)? And perhaps it just isn't very unusual in the first place? Maybe you should think about things like that, before you go bothering Mr Darwin?

Further research, and a grant to match, are urgently required. Meanwhile, I'm more pleased to have inherited the ability to nap at will from my maternal grandfather, a skill most pleasant and profitable for sailors and academics alike.

What I hadn't realised was that he also made observations on Louisa's own family - which happens to be mine too - although these were rather less obnoxious in character. He reported to Charles Darwin in 1871 that Louisa's father, George Butler (for more on whom, see here), had a peculiar way of napping:

[He] used to take after dinner naps in his arm chair, during which he had a strange habit of raising & laying his forearm across the top of his head,—whence, as he nodded, it dropped in front of his face, striking his nose as it fell, usually awakening him with a start. The bridge of his somewhat prominent nose was frequently sore & sometimes raw from this curious habit.

What was interesting to Galton was that this quirk was not confined to George. His son Montagu, and one of Montagu's daughters, had the same habit - and in another letter a few years later he was able to confirm that the same was true of the child of another of George's children, Spencer. He thereupon produced the following map of the heritability of napping with one's arm on one's head:

Here, he puts George at the top of the tree, but there's no particular reason to suppose that the arm-napping mutation started with him. Perhaps it was also to be found in the descendants of George's brother Weeden, my own great-great-great grandfather?

Now, I don't nap in this way myself (though I do often assume this posture when lying in bed), but I'm sorely tempted to do a round-robin of my various cousins.

On the other hand, Francis, perhaps Montagu et al. got the habit from observing their respective parents (or uncles or cousins)? And perhaps it just isn't very unusual in the first place? Maybe you should think about things like that, before you go bothering Mr Darwin?

Further research, and a grant to match, are urgently required. Meanwhile, I'm more pleased to have inherited the ability to nap at will from my maternal grandfather, a skill most pleasant and profitable for sailors and academics alike.